Is government spending driving inflation?

Yes, and it's worse than you think

Inflation is running hot in Australia. Headline CPI inflation surged to 3.8% y/y from 3.6% y/y in the prior month. Trimmed mean inflation, which aims to eliminate volatile items from the measure, much like ‘core inflation does’, also increased to 3.3% y/y from 3.2% y/y. But why? And, is government to blame?

The simple fact is that government spending is a key inflation driver. It is not the only driver. Jim Chalmers insinuated that it is not a driver at all. Is he correct, or is it just spin?

Let’s start with the obvious. Jim Chalmers suggested that because the RBA had not called out government spending, the RBA therefore thought that government spending was not an issue. However, Jim Chalmers fundamentally misunderstands the RBA. The RBA is reticent to explicitly call out government spending. The reason is obvious: the RBA does not want to be seen as partisan or wade into politics lest it jeopardize the RBA’s perceived independence.

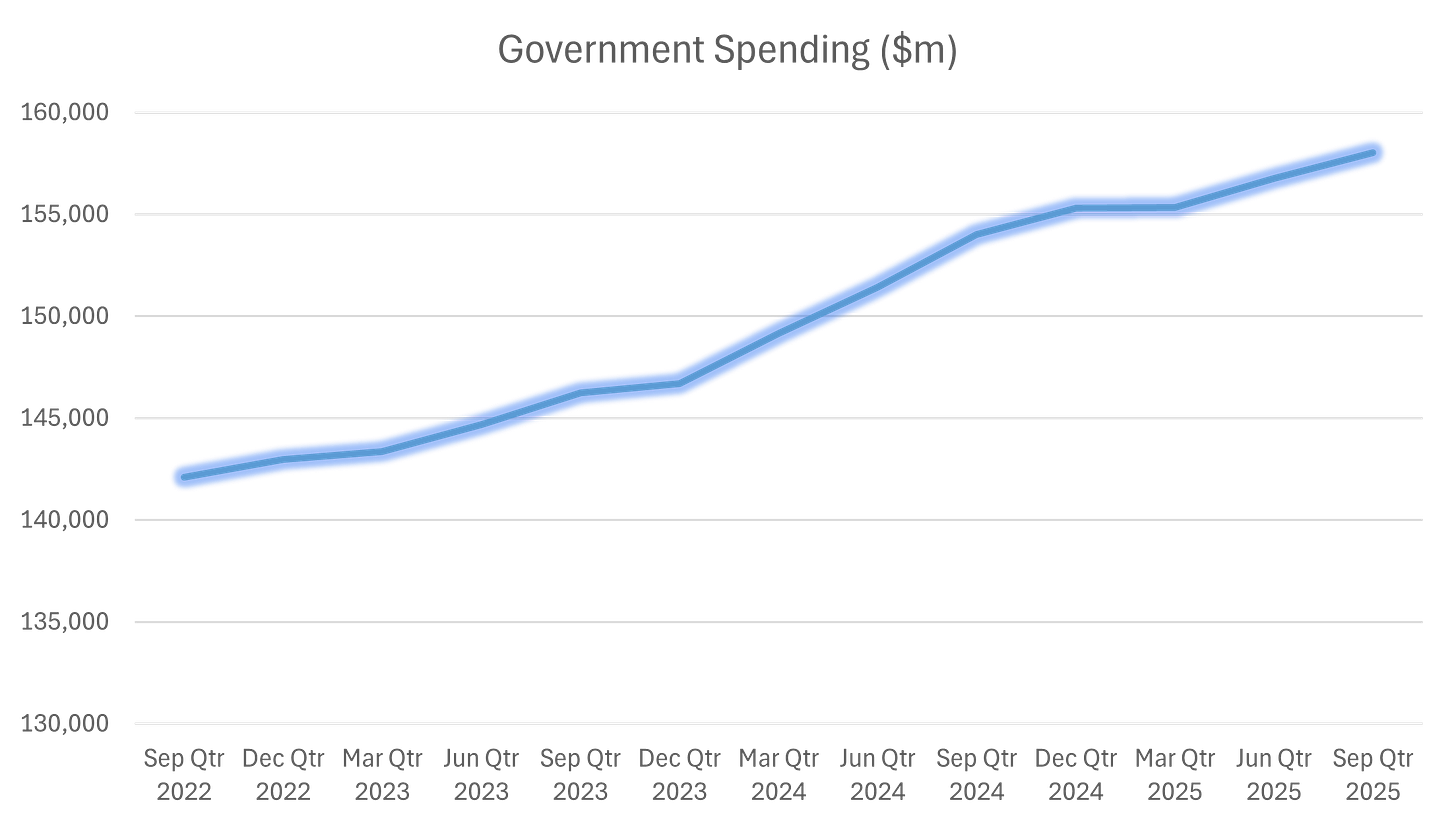

Government spending has consistently increased since Anthony Albanese assumed office in 2022. Of course, inflation can partly explain the increase. However, this is chicken-and-egg. The decision to keep spending at the newer higher prices just ensures that demand continues and stops inflation self-correcting. That is, when consumers are price-sensitive, the cure for high inflation can be inflation itself as high inflation damps demand, which helps prices to normalize. Self-correcting mechanisms are often insufficient to correct inflation, hence why central banks also use interest rates to force such a correction. But, if the consumer – here the government – keeps spending that self-correcting mechanism does not work.

The short of it is that government spending supports demand, which supports inflation. Now, one might wonder how government spending influences housing prices. Or recreation. Or transport. Well, when the government spends money, it buys raw material inputs and labor. These are the same inputs that would go into housing construction, inter alia. Thus, input prices increase across the board, which then drives inflation in myriad areas.

But it gets worse.

Government spending is inherently less efficient and productive – and thus more inflationary – than private sector spending. There is an adage that when you spend your own money on yourself, you care about cost and quality, but when you spend someone else’s money on someone else, you care about neither cost nor quality. Thus, when a politician spends tax payers’ money to build a tunnel for someone else, they have less incentive to be efficient. And indeed, their incentive is to build something to generate votes even if the economics stack up.

The problem is agency conflicts. Agency conflicts arise whenever you hire someone to perform a job. Here, the agent (i.e., employee) might have an incentive to shirk, waste resources, or grow the department inefficiently so as to look more prestigious.

Agency conflicts, and the associated waste, are especially bad in the public sector. There are several ways to combat agency conflicts. First, you could discipline workers (or executives). In the private sector, this can involve monitoring, and firing. This is especially the case for more senior executives. Second, incentive contracts can drive better performance. But, government departments are notorious for poor incentives, stagnant wages, and a lack of bonuses. Thus, as a worker becomes more experienced, the main way to get a “raise” is to work less hard or direct resources in ways that implicitly benefit the worker. Thus, when 80% of new jobs are in the non-market sector, you get more inefficiency.

Examples abound. Let’s take the Machete Bins in Victoria. The machete bin program cost some $13 million, involving a massive advertising and education program, and the installation of 45 bins to collect machetes. That’s a staggering cost. Each bin might have cost a few thousand to construct, but the all-in cost amounted to some $300,000 per bin. But not only that, the policy is absurd: machetes can easily enter Victoria via its land-borders, it is very clear that criminals would not deposit their machetes, and it is obvious people could just replace a machete with a meat cleaver if they wanted to do crime. The short of it is that the government spent tax payers’ money, and did so inefficiently, in order to be seen to do something. Jacinta Allan spent our money, pursuing a nonsense policy, to try to get votes. This is the problem with government spending.

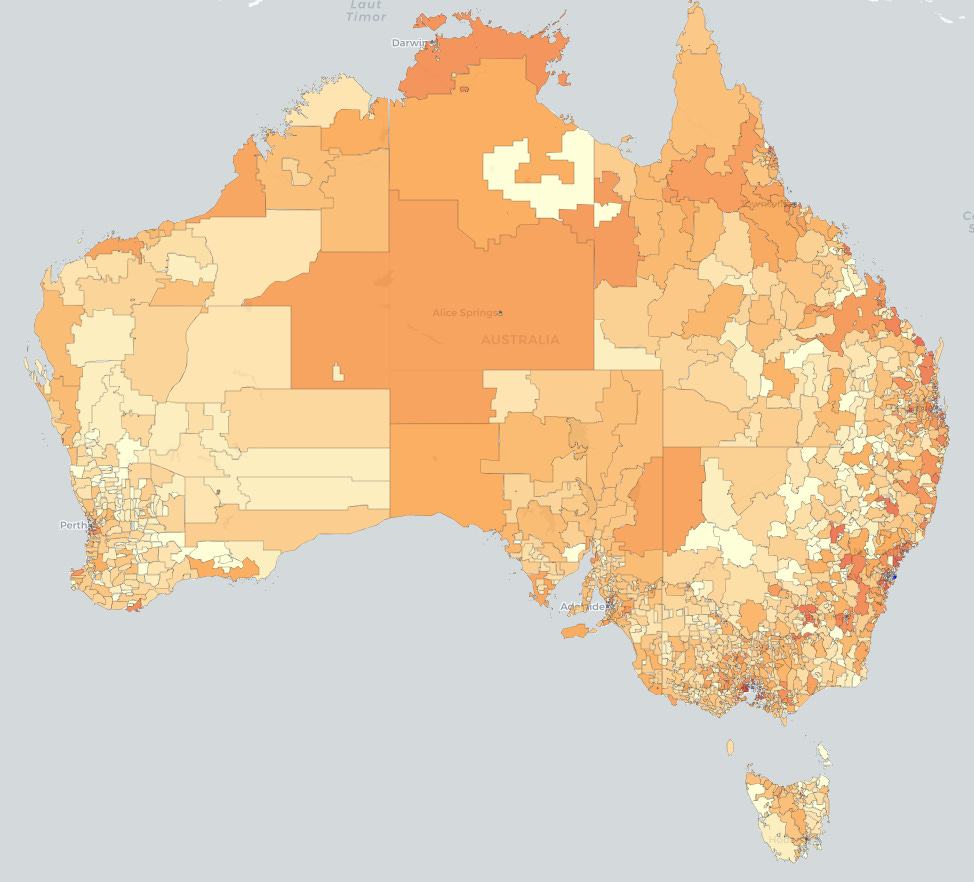

Then there is the NDIS. It is growing at more than 7% pa. This is simply unsustainable because it is growing faster than the economy. Notably, there are some very curious clusters of NDIS providers in different regions. A curious mind might wonder precisely why, whether demographics explain the clustering, and whether there is wastage or largese. The raw NDIS provider data is available here, and to premium subscribers to download (see end of article).

The inefficiency can be unfortunately self-perpetuating. An ambitious bureaucrat might well want to be promoted or earn more money. How do you achieve that, by running a larger team with a higher budget? So, what do you do, you create projects to justify a higher had count and greater expenditure, thereby making yourself look more important. It certainly happens in the private sector. But economic reality has a way of catching up with executives who burn shareholders’ cash. By contrast, the public sector solution is to try to find more money.

Jim Chalmers is looking to make this worse. Division 296 looms on the horizon. It is a tax hike to enable the government to spend (or waste) more money. Similarly with the capital gains tax review. But, the problem (inter alia) is that this just soaks up money from a productive user to an inefficient one. And, let’s not forget bracket creep.

The net result is that government spending both increases demand and that increase is inefficient relative to keeping the money in the private sector. Indeed, if Australia is serious about driving productivity, the government must stop hoovering up revenue, only to spend it inefficiently, and must seriously look to cut income, corporate, and capital taxes, which will drive expenditure to its most productive home.

Note: For those of you who would like to expore the weirdness of NDIS/social service distributions, you can check out the data if you are a premium subscriber (see below).